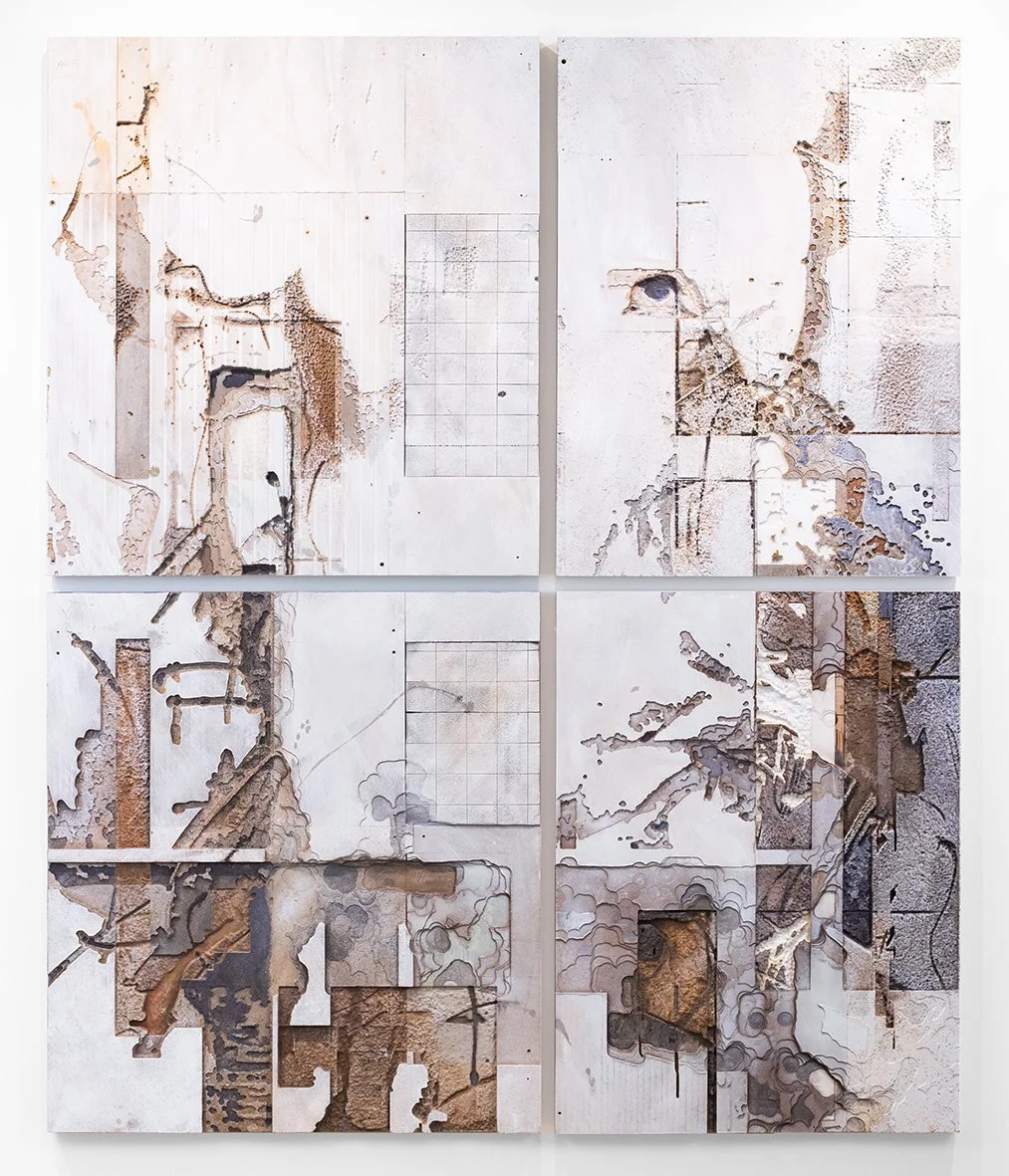

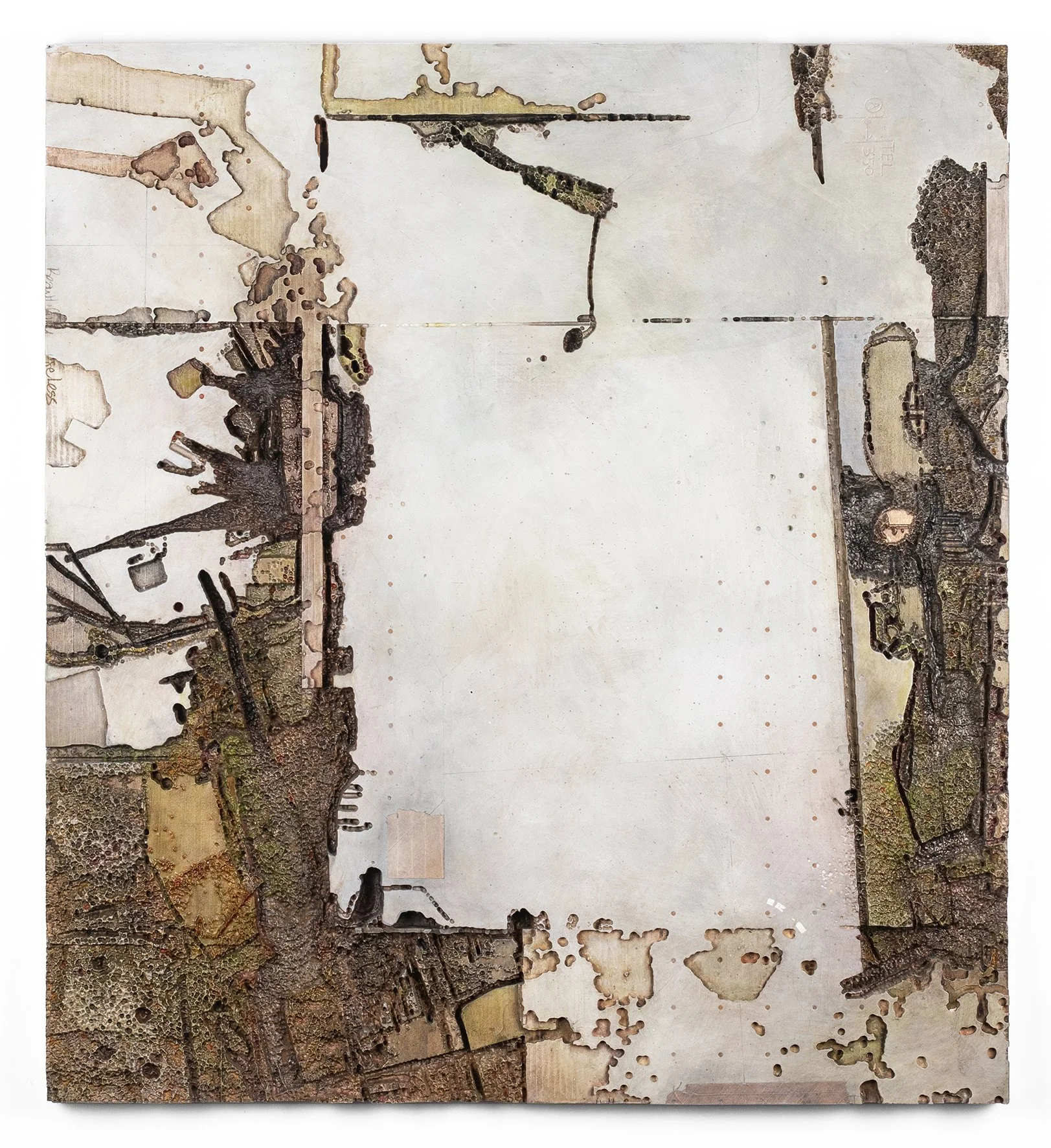

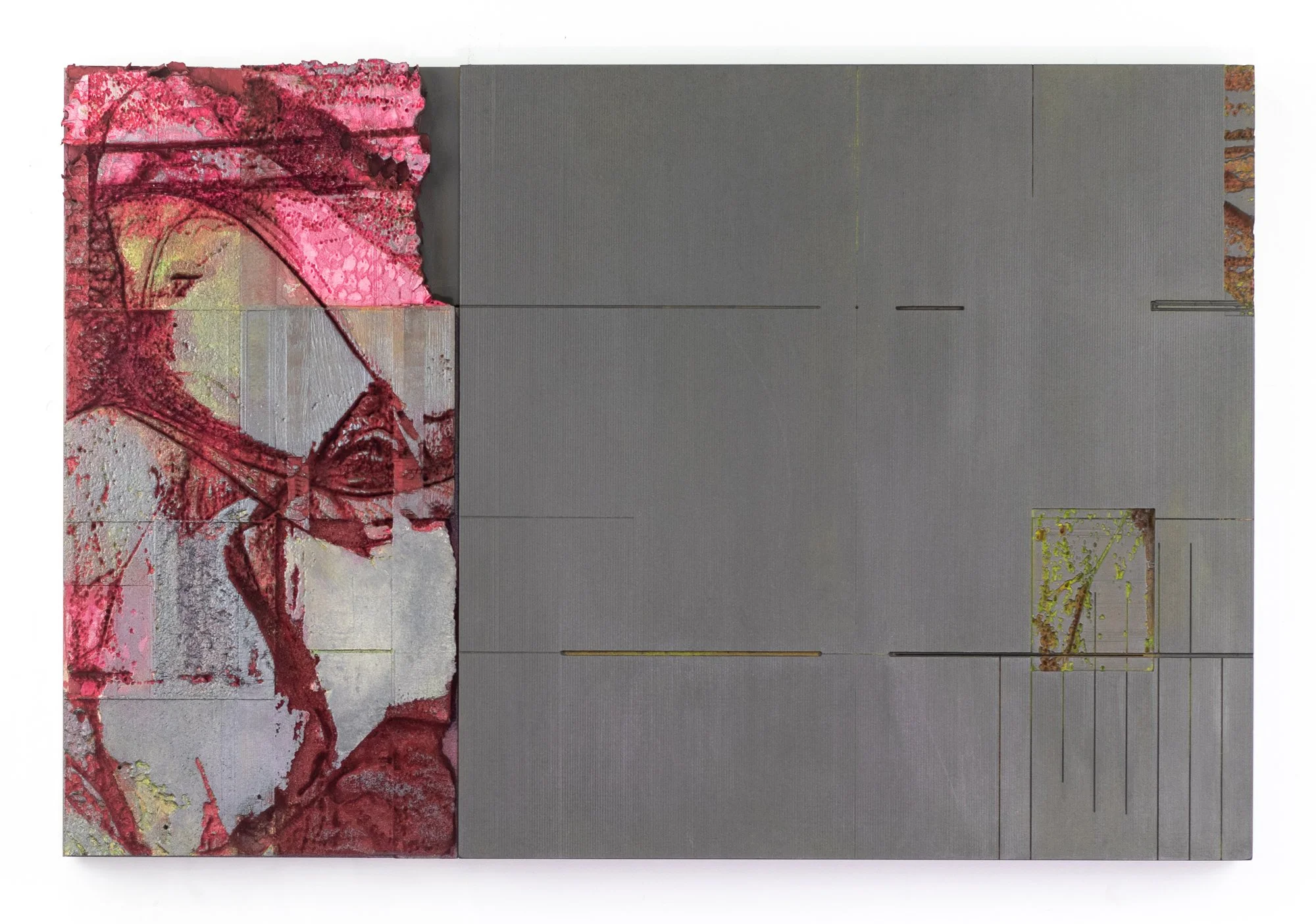

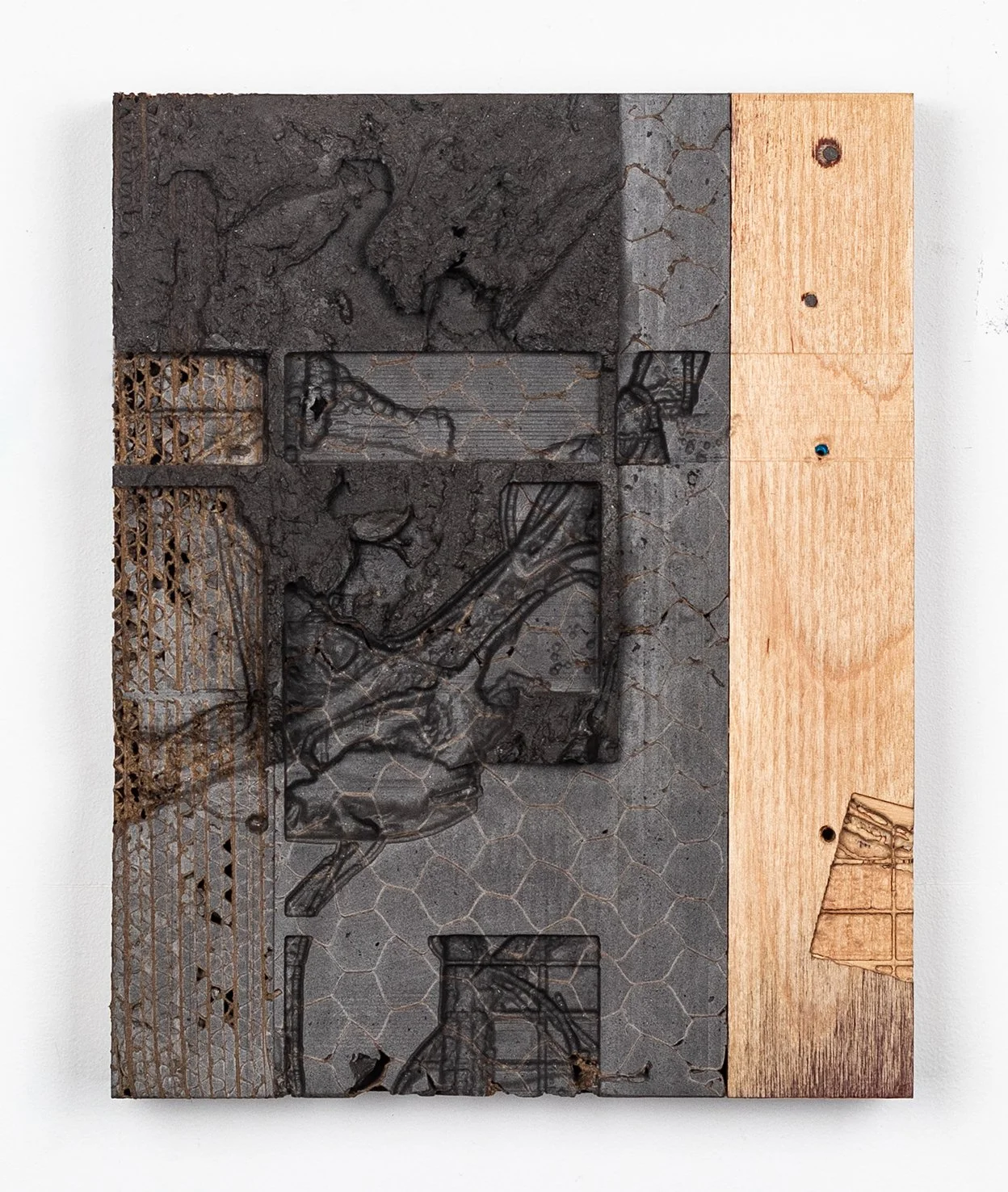

Presence series 2023 - 2025

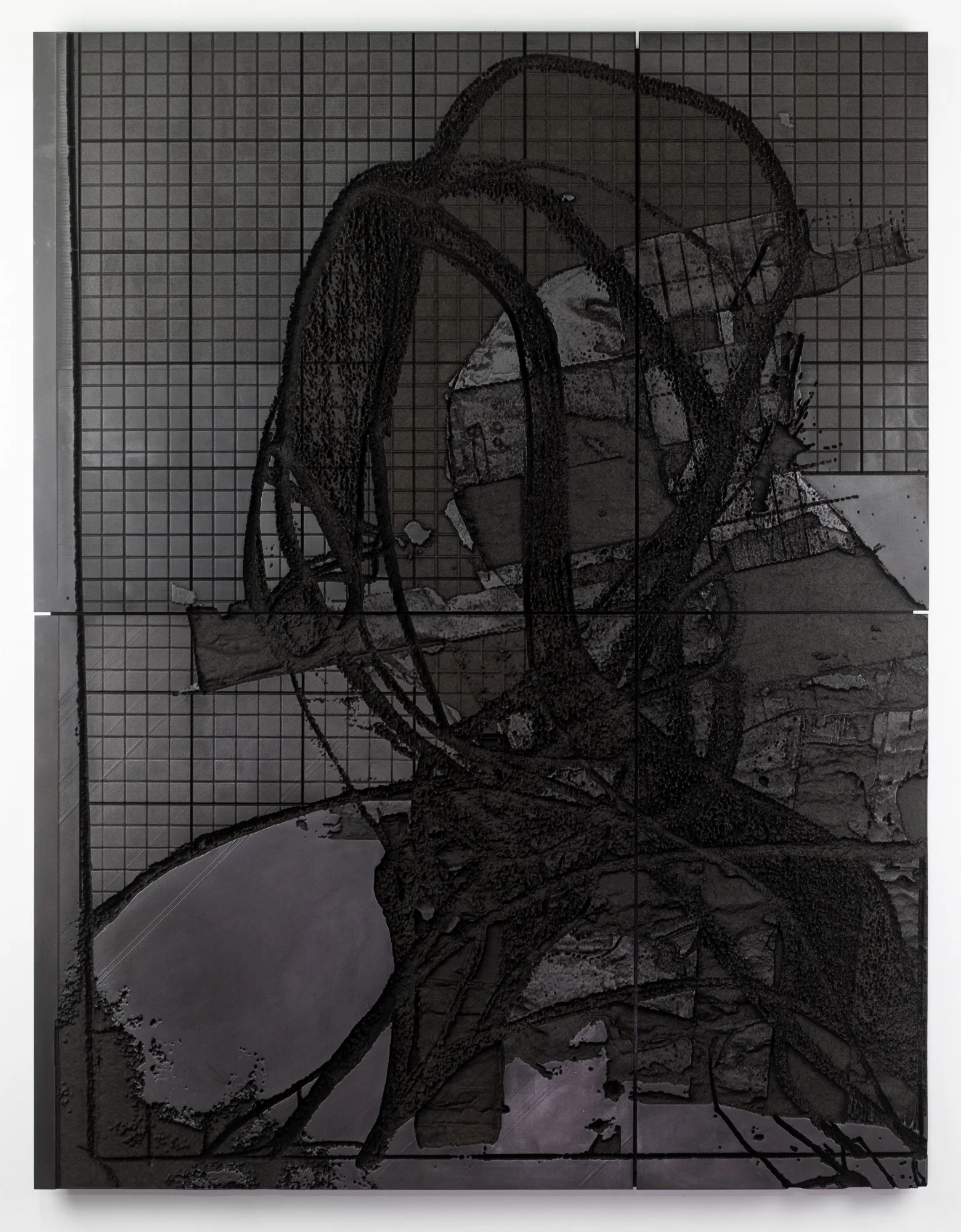

Presence - Pr25-02

‘Presence’ exhibition 2025 at Art Atrium 48

Presence - Pr24-24 (detail)

"There are few ways in which works of art today can escape classification and definition, but James Gardiner - who goes by the pseudonym, fahn - is blurring the boundaries. On the most fundamental level, Gardiner’s works are drawings, but they are also sculptures, paintings, and architectural models. It doesn’t require much imagination to see them as maps or diagrams."

Quote from John McDonald's catalogue essay for the exhibition 'Presence'

Presence - Pr24-17

Presence - Pr23-10

Presence - Pr24-05

This work explores unknowing and presence, through a play with ambiguity and 'the perspectival flip'. Two series, 'Sentience' floor drawings and 'Presence' digitally fabricated relief paintings, investigate our shifting perception in the digital age.

Rooted in gestural abstraction, these works invite viewers to engage with multi-perspectival ambiguity. The 'Sentience' series begins as gestural floor drawings, consciously created without intention. The 'Presence' series evolves these drawings through collaboration with a 3D digital cutting machine, creating deeply indeterminate artworks.

This conscious engagement with ambiguity, blending digital and analogue techniques, aims to create moments of contemplation. Viewers are invited to recognise the unknowing in our shared human condition and connect with the present moment.

Fahn

Presence - Pr23-01

Presence - Pr23-04

Presence - Pr24-26

Presence - Pr25-01

‘Presence’ catalogue essay by John McDonald 2025

There are few ways in which works of art today can escape classification and definition, but James Gardiner - who goes by the pseudonym, fahn - is blurring the boundaries. On the most fundamental level, Gardiner’s works are drawings, but they are also sculptures, paintings, and architectural models. It doesn’t require much imagination to see them as maps or diagrams.

Gardiner’s creative processes are equally complex. Using a CNC machine (ie. Computer Numerical Control) he doesn’t simply make marks on a flat surface - he draws into the surface. Each drawing is an excavation that leaves a plane divided into layers, like a model of an archaeological site. The artist works back over these layered pieces, painting and shaping forms that hint at recognisable motifs, without ever reaching a conclusive final form.

It's that glimpse of recognition that fascinates Gardiner, although he admits his work is fundamentally abstract. He has long been engaged by the phenomenon of Pareidolia – the human capacity for seeing images and patterns where none exist. The Man in the Moon is one example. Reading tea leaves is another.

In the most basic fashion, we tend to think of works in a horizontal format as ‘landscapes’, and vertical ones as ‘figures’, even when there is little evidence to support this feeling. This is one of the reasons Gardiner prefers formats that are slighty off-square, if only to thwart that instinctive association. He sets out to draw in a spontaneous, unselfconscious manner, referring to the Zen concept of mu-shin or “no mind”, which really means liberating oneself from the buzzing thoughts and residual emotions that underpin our daily actions.

Yet when he looks at the results of these no-mind gestures, Gardiner recognises that many viewers will see heads or faces overlaid on landscapes. It’s almost irresistible with Presence Pr23-01, or Presence Pr23-04. Quite by coincidence, the latter bears a striking resemblance to a stump painted by Fred Williams in 1976, which is an excellent example of pareidolia in its resemblance to a human head.

One imagines that for Gardiner, who was an inventor and architect before he devoted himself to art, it requires a huge effort to break away from an analytical way of thinking. His pseudonym, fahn, is an emblem of that effort, based on the Cantonese ‘sic fan’ which means to eat rice, or as Gardiner prefers, “to remember the base”. Just as a Chinese meal is unthinkable without rice, Gardiner is reminding himself to focus on those bedrock aspects of art and let the viewer supply the meanings.

He would probably agree with Marcel Duchamp, that “a work of art is completed by the viewer”. This implies that whatever the artist’s intentions, the viewer is just as likely to come up with their own interpretation – sometimes a better interpretation. Those artists who act as control freaks, wanting us to understand their specific, urgent messages, are often defeated by the viewer’s unruly imagination. This is not to say there aren’t a lot of viewers who turn anxiously to the wall label or the catalogue entry seeking guidance, but this doesn’t mean there is only one “true” way of reading a piece.

Gardiner subscribes to the view that a work of art is essentially an open-ended fiction. In this exhibition these fictions may be impressively solid, but they are not any one thing, and there is no attempt to address any of those social and political issues contemporary artists find so entrancing.

It is, however, hard to avoid speculation, and to me these works are maps of the mind – mappa mentis rather than mappa mundi. As early cartographers had to find ways of filling in blanks on a map of a world only partially explored, so too does Gardiner ask us to add our own details to these ambiguous objects, at once so suggestive but reluctant to reveal their ‘true’ identity.

As maps, Gardiner’s works are ruined maps – to borrow the title of a 1967 philosophical crime novel by Kobe Abe. We look at these tableaux - composed of a bewildering variety of materials, carved by machine and finished by hand - and see sharply defined spaces that have been routinely broken or overrun. Gardiner the architect and inventor may be accustomed to precise calculation, but Gardiner the artist practices a style of drawing that refuses to conform to all those grids and straight lines.

With some of these pieces we adopt a drone’s eye view of what could be a room, a town square or an orderly set of fields upon which the artist has laid down lines that whip around with the verve of a Chinese dragon, or craters that could have been caused by bombs or natural disaster. Call it a fight or a dialogue, but what we see is an artist battling counterintuitively against his own instincts. The works bear the scars of a ferocious dispute between those two poles that Pascal dubbed the Mathematical and Intuitive minds – esprit de géométrie and esprite de finesse.

If it seems Gardiner has hinted at a motif only for the pleasure of disrupting it, this reflects his own flight from the severe rationality of science and technology. He has left it to us to find the monuments in these ruins.

Presence - Pr25-03